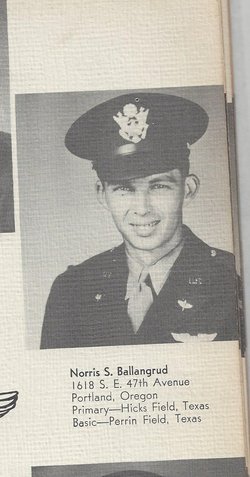

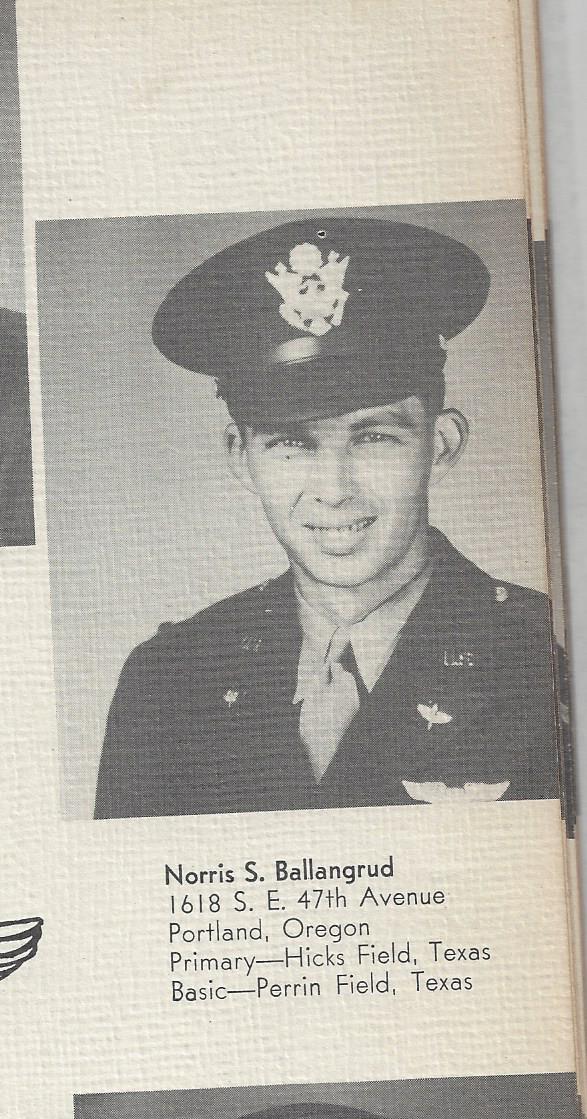

Memorial Service To Honor Flier.

A memorial service for Lt. Norris S. Ballangrud, who was killed in France, January 21, 1944, will be held at Bethlehem Lutheran Church Sunday at 11 A. M.

Lt. Ballangrud, who was pilot of a B-24, attended school at Silverton and at Benson Polytechnic School and was employed at the Bonneville Power Administration before his enlistment.

He is survived by his wife and daughter, his mother, Mrs. Dina Ballangrud, a brother, Arthur, of Kelso, Wash., and sisters, Alice Ballangrud, Della Stranix and Margaret Coppin.

---------------------------------------------------

Co Pilot 1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen KIA

Body Identified

Home: Portland, Oregon

Squadron: 68th 44th Bomb Group

Service# 0-681300

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Pilot 1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen KIA

MACR #2359

Target: V-1 Sites, Pas Des Calais Area, Escalles Sur Buchy, France

Mission Date: 21-Jan-44

Serial Number: #42-7514

Aircraft Model B-24

Aircraft Letter:

Aircraft Name: VALIANT LADY

Location: France

Cause: enemy fighters.

Crew of 10 7 KIA 3 POW

Once again the weather was poor, with heavy cloud cover over most of this area of France. Normally, this should have been a relatively “safe” mission, being so close to the English Channel, but it turned out to be VERY costly. The 66th and 68th squadrons had their own specific target to hit and were determined to do so in spite of the clouds which were covering the small V-1 launching sites. Bombing altitude was at a very low 12,000 feet.

MACR briefly says that this aircraft, was hit on the sixth and last attack by the enemy fighters. The time was 1526 hours. This plane was seen to nose up and over the formation with the waist position burning profusely. No one reported seeing any parachutes. This was their 18th crew mission. Sgt. Leo M. Tyler, ball turret gunner, was (apparently) reported incorrectly as POW. He was later reported killed at Poix, Somme, France by the Department of the Army. Only three men survived to become POWs: Allen, Cleary, and Hoeltke. Relatives of Donald R. Hoeltke reported that only three men got out of the plane and one of these was very seriously injured (probably Allen). The plane was shot down in the area of Bruay, France. The crash site is located at Neuville-Ferrieres, 4 miles SSW of Neufchatel. When Lt. Hoeltke hit the ground, he was immediately surrounded by troops with about 18 bayonets shoved at him. There was no possibility of any attempt at evading capture. He was taken in for interrogation according to the usual procedure, but Donald learned that his interrogator had worked in the U.S. for several years, knew Al Holderman of the Gannett News, and had returned to Germany as a private pilot. Later, he was grounded and due to his excellent English, was made an interrogator of English and American POWs. Lt. Hoeltke’s widow stated that he had told her he thought that three men got out and parachuted, but one was critically wounded and could have died. He knew that Sgt. Tyler had been made a POW; their site of capture being about 45 miles south east of Calais, France. Lt. Hoeltke was later sent to Stalag Luft I, Barth and remained there until the end of the war. Lt. Cleary’s name was not mentioned. (See his account later on.)

Richard Allen wrote the following, not long before his death in 1947: “We were attacked by about 30 fighters over France near Path Colay on 21 January 1944 and shot down. I believe we went over our target about six times but I couldn’t be sure. Before we were hit by the fighters, I was flying Radio Operator (my position) when Sgt. Ostenson came up front to fix some trouble with the nose guns. He was our armament gunner. The pilot told me to take over his (Sgt. Ostenson’s place) until he came back; that was the left waist. “I no sooner plugged in my electric suit when the attack began. There were about seven planes in our squadron and I believe six of us got knocked down. When we got hit, I was shot through the leg and received a bullet in my spine. The other waist gunner S/Sgt. Victor Adams was also shot and as far as I could see, he was dead. The plane was all on fire from oxygen burning, and it brought me to my senses and I put my chute on and pulled myself up on the waist window. My interphone was shot out and I couldn’t tell if we were going to make it back or not. The plane

was vibrating violently. I saw Sgt. Playford run out of the tail turret, and he was all on fire. At the same time, Sgt. Tyler, our ball turret gunner started to come out. It all happened within a few seconds and in that time, the plane seemed to roll over and I let go and went out. I didn’t notice whether they had their parachutes on or not. I did not see Sgt. Dickinson as he was up front in the top turret. When I got on the ground, I was picked up and taken to a hospital where I saw my bombardier, Lt. Hoelke, and Lt. John Cleary (navigator) for a few minutes. Lt. Hoelke and Lt. Cleary had bad ankles from the parachute landings. Later, in the hospital, I met a crewmember from one of the other planes in our squadron and he said he saw our planes going down in a spin with flames coming out of the engines.”

The following information comes from a document written by a graves registration investigator named Howard E. Ephraim: “Contact was immediately made with the Mayor of Neuville-Ferrieres, Mr. Gonse, who was particularly well informed on all details pertaining to the crash of A/C 42-7514. He stated that he had seen the plan e crash, that three men bailed out, and that six men were removed in caskets by the German troops. That accounted for nine of the ten-man crew. He further declared that eight days later a dog, which had been attracted by the odor, indicated an additional set of remains which had been obscured by a sheet of aluminum. A guard had been posted at the wreckage of the plane and eventually all of the wreckage above ground was removed by German ordnance crews. No one at Neuville was aware of the fact that this last remains was removed, hence, it is considered possible that it was buried at the scene of the crash by the ordnance team. This account was verified by Mrs. Lefebre who also gave to the investigator the identification tag of Jack Ostenson, one of the unresolved casualties in the crash. This tag was found at the scene of the crash by Mme. Lefebre. A few days later, the Germans removed the wreckage. This definitely fixes the identity of the plane as that of A/C 42-7514.”

Lt. Cleary wrote the following account about the events of January 21, 1944: “Gentlemen, your target today is a milk run, a V-1 site, southeast of Neufchatel, France, only ten minutes over the enemy. Area escort provided by the 8th Air Force Fighter Command and British Spits. Altitude, 10,000 feet. Departure point is southeast corner of England. The 44th BG flight of 24 ships in two 12-ship boxes, will split into two flights of six each. Flight A, lead by Col. Dent; Deputy Lead Lt. Gilbert. Flight B lead by Lt. Williams, Deputy lead Lt. Mathisen. Good luck men. See you when you return. “Deputy lead, Flight B crossed enemy coast at Fecamp, on course, at altitude. The boxes have split for the different targets, and all are now in separate flights. I.P. in sight, three minutes to target. Light, scattered cumulus below, visibility .8. No flak, no fighters, all is well. Target in sight, obscured by small cumulus, so fly 360 degrees to let it clear. Time 1500. Flew continuous 360s, target is still isolated, but clearing. Time 1550. “Suddenly, ‘Waist to crew. Waist to crew. Enemy aircraft at 2:00 o’clock, low.’ Immediately B Flight tightened up the formation and hoped for the best. A quick glance revealed approximately 16 Me 109s and 35 FW 190s. A Flight was approximately three miles ahead and coming off the target. Do not believe they ‘dropped.’ “Then the enemy was up and because we were on the bomb run, they concentrated on us, leaving A flight alone. I knew from the ship’s vibration that all stations were manned and firing, but they are attacking from about 4 to 5 o’clock, low to level, working us over from the rear.“From the tail turret came the report (1) ‘Spelts going down, (2) There goes Starring. (3)They’ve got Howington!’ We were still on the bomb run and suddenly from the bombardier (Lt. Hoelke) came ‘Bombs Away!’“I heaved a sigh of relief to know that we were rid of them. Bank away to the left and head home. Then, over the interphone from the pilot (Mathisen). ‘Keep an eye on Sobotka. He’s hit.’ I verified this, noting all reports in the ship’s log, got a visual fix and informed the crew that if we could hold out for five more minutes, we would be clear and over the Channel to safety. I requested the pilot to summon assistance from our escort. He replied that he couldn’t do so. That was up to Lt. Williams in the lead ship. “Waist gunner then called in that Sobotka was going down, and then from the pilot, ‘They’re coming in again. Let’s get some of the bastards!’ All stations were firing and the ship gave a terrific lurch, banked to the right, and went into a slow, descending spiral as the enemy raked us from the nose to tail. A 20-mm exploded between the cockpit and nose, showering Lt. Hoelke and myself with light fragments. ‘We’ve had it!’ shouted Hoelke, as we checked things, and found all communications out. Our Nose Gunner, by now, had his turret aligned (so he could get out). Hoelke slid past me to the escape hatch, passed me my chute, and with the nose gunner behind me, we prepared to abandon ship. “I pulled the emergency release, and as the escape hatch flew away and to save time for the others, I stepped out into space, parachute in hand, intending to secure same during my fall. To my amazement, I still hung suspended in space, shoulders even with the fuselage bottom, with my head in the ship!! I was caught on my extra long interphone extension. Reaching up, I pulled myself aboard and while I cleared my phone, Hoelke reached over and put my parachute on me. As I re-jumped, I heard the nose gunner shout, "My chute! My chute!!" I fell through the air, spinning like a top while experimenting to find the best position. This proved to be on my back. “I felt like a feather in the air – there was no feeling of resistance, no planes were to be seen except my own, spinning. It crashed in a flaming roar. No other parachutes were in sight, and I felt sick about the other men. “There was no more gunfire to be heard, absolutely no sound at all. A celestial calm seemed to prevail. but coming to with a start, I pulled the ripcord. From my now upright position, I realized my chute was satisfactory, and the calm, sunlit terrain of France was sweet below. “As I neared the ground, I could see a farmer calculating my angle of fall, and as I neared there, he was reinforced by a dozen others. Then I clearly saw they were Germans of the Luftwaffe all around, with machine gun pistols. As I turned to keep them in sight, I hit the ground and my right foot buckled under me. The Germans were on me in a flash, spread-eagling me, they conducted a rapid search. Completed, I was assisted to arise. I reached to release my English type parachute harness, and seeing same was in the unlocked position, I grew suddenly weak. The Germans had to support me to prevent my collapsing. Had I but touched that buckle in the air, my parachute and I would have parted company! “Escorting me to the roadside, I was seated on the bank while a medical orderly administered some necessary first aid. My right foot was severely injured. Cutting away my flying boot, he applied a cold compress and assured me that there were no broken bones. My left arm was injured from a 20-mm, halfway up the arm from my wrist. It was just like a cut from a keen razor. Washing same, he applied a disinfectant and tied up same with adhesive. “I was then carried by my escort to their headquarters, and so learned that I was back at Neufchatel, having floated in my chute a distance of 35 kilometers from the Channel at Deippe. “Here I was the object of much curiosity and many would stroll by, then quickly snap a picture with their cameras. I was detained there for two hours, given my first cup of Ersatz, and met my first German Officer. He strode to the phone and having got his connection, yelled back and forth so loud and fiercely, I was sure they could hang up the phone and still continue the conversation. He studied me a moment, and then gave what I realized to be a description of the Group - Squadron insignia on my A-2 (flying jacket). Then, hanging up, he strode to where I sat and barked in excellent English, "What is the strength of your Group in men and ships?" “I just sat there and wondered if he really thought I would answer that. Evidently not, because as I silently sat there, he spun on his heels, marched out. After this, I relaxed, slept for half an hour, and then I was awakened by the entrance of a German field gendarmerie. He was the first adult-looking man I saw since being captured (all of the others being boys of extreme youth). “He took me in charge and seeing I could but hobble, he picked me up in his arms and carried me out to a car very similar to a Willys, where I promptly fell asleep again. This was probably much to the relief of my guard and his chauffeur. I awoke in Rouen and was taken to what appeared to be a Catholic hospital. “Upon being carried inside, I was overjoyed to see Sgt. Allen, my radio operator, who was in action as a waist gunner that day. He was lying on a stretcher, but sat up and gave me some additional information on the crew. Lt. Hoelke, bombardier, had been there recently, and like myself, had but minor wounds. No one else got out of the ship. The plane itself had communications out, hydraulics out, and the tail section was on fire. Richard, although shot through his body and legs, looked okay, and should, I believe, recover. To date, however, I have been unable to get any word of him. Taken to another room, I was treated for my leg and arm, given some vile potion to drink. My guard carried me to Police Headquarters in town where I met Lt. Hoelke and Sgt. Andrew Ross, of Sobotka's crew. Having the office to ourselves, except for a Jerry, who seemed to be acting as C.Q. and who talked to us by means of a German-English-French book of vocabulary, we talked. “We discussed the situation and came to the conclusion that the nose gunner may have had his chute on the escape hatch and same was lost when I pulled the emergency release; or else he left it at his regular position in the waist, and failed to get back there in time. The Germans had caught us square in the cockpit, getting both the pilot and co-pilot (Ballangrud), then raking the ship back clear to the tail. Like myself, Lt. Hoelke was captured as soon as he hit the ground. “We were finally served a meal of a hot, hideous soup, Ersatz and bread, which was the national Jerry war loaf. I promptly dug into same and immediately became nauseatingly sick, so that I left the rest of it untouched. The prospect of life on such stuff was distinctly unpleasant, and it was a relief when they showed us to a bed. It was a double bunk, with straw ticks, permitting four occupants in a cell 8' x 10'. I shall be eternally grateful to Sgt. Ross who took off my shoes, wrapped the blanket around me, as I was violently ill. “An hour later, the lights came on, chain and bolts withdrawn, and Lt. Fred Butler, navigator of Sobotka's crew, was shown in – to complete our happy home. “I awoke the next day feeling a new man, the shock and dazed condition having passed away. We were given what was to become our standard breakfast – Ersatz and bread. We loafed around the office being an object of curiosity to all the Jerries and French workers. Due to the heat in the room, I removed my A-2 jacket and coveralls. A sad mistake, because shortly thereafter, a guard detail came in and motioned us out, refusing to permit me to take my A-2. I have often wondered if it was recovered by the capturers of Rouen or kept by the Jerries as a souvenir. “We were ushered into an open truck with six guards, and transferred to the Bastille of Beauvais, a building with a 4 x 8 cubicle containing the usual prison bed, a small stove and a bedpan which stunk to high heaven. The room was daily swept out and stove remade by a British Senegalese, a slim giant who spoke a soft, musical English. He was captured in Africa, had made three escapes – one clear back to Africa, which was now controlled by Rommel. He told me about prison life – mail, Red Cross parcels, etc. Just before we left, he gave me a half can of Corn Beef. It was delicious, as by that time we were famished on the Jerry diet. “Here, I noticed that the Germans, despite a search, had overlooked my wallet, taking it out and destroying my A.G.O. card and secreted some 12 pounds Sterling in my belt. Lt. (William) Jones, Bombardier from Starring's crew, joined us here. “After four days at this hostelry. we started on our journey to the "Vaterland" via Paris. All was peaceful and serene in Gay Paree. Everyone seemed well dressed, well fed and fairly content, although we received many a sympathetic glance. We traveled in a compartment to Frankfurt-on-Main and were taken to Oberusal, a small village ten miles from Frankfurt. This was the Jerry interrogation center for captured Allied airmen. After a thorough search, which found the money in my belt, we were again thrown into solitary confinement. Next day, I was given a questionnaire to fill out, giving my name, rank, serial number, and home address. I left the remainder blank, and returned it to the Jerry. I was then informed that I would go to interrogation immediately. So preparing for a third degree of the worst sort, and all set to give battle, I was taken to another building and introduced to my Grand Inquisitor. To my amazement, he greeted me like a long-lost brother and spent the first half-hour discussing his wife and family in New York, as well as the fine times he had at Jones' Beach. “After that he switched to questioning: Route overseas, Personnel of the 44th BG, Cadet School, O.T.U., bases, and members of the crew. Upon refusing any information, he said that he knew the crew and if I would verify it, he would give me any information he had on them. All this time he was "feeding" me some abominable cigarettes, which being my first in a week, I thought were grand! “He produced a list of names and positions - and sure enough, it was the entire crew. I acknowledged it, and was told that all were dead except Hoelke and myself. He had no information on our radio operator, Sgt. Allen. He then produced a thick manual and spent a half-hour telling me all about my Group, both combat and ground personnel, etc. He told me we were starting to receive the new B-24 H & J's, knew the exact routes for flying overseas, training schools in the States, O.T.U. bases, etc. He concluded by saying, "So you see I actually know more than you do!" He was correct. He then remarked as he dismissed me, "Your Air Force is about to separate from the Army and Navy, similar to the R.A.F. and Luftwafte, and your new uniform is a light blue gabardine." To date, I have heard nothing to verify this. “I was returned to solitary and usual prison lunch at 1:00 and to my surprise, was again taken back to the interrogator. This time to meet half dozen German navigators who could speak no English. Through the interpreter, they requested info on "G,” the reliability of metro info, radio bearings and fixes. I grinned, smoked their cigarettes and explained that we depended strictly on D.R. and Pilotage, if weather permitted. They quickly lost interest and as I was dismissed, the guard was instructed to permit me to wash and shave. I was then told I would move to the Transit Camp in Frankfurt for shipment to a POW camp. “After a week’s time, the wash and shave was a heavenly gift and a natural necessity. Later the guard brought a book to my cell and the thought of electric lights was like looking forward to Christmas. He must have been exercising a sadly neglected sense of humor or else sincerely thought an airman could see in the dark. “That night was my first experience on the receiving end of an Allied Air Raid. The RAF came over, but it was merely a nuisance raid. Thirty Mosquitoes, with a "Cookie" each, (60 tons - some nuisance!). Locked in my cell, I felt like a caged animal. Next day I was transported to a transient camp at Frankfurt and received immediate medical attention, followed by an honest-to-goodness hot shower and a fine, hot meal of Corned Beef, mashed potatoes, cake, coffee, and cigarettes. Hooray! God's in his Heaven, All’s well with the world. “Here we had an air raid shelter, of which we made much use, especially on January 29th, 1944, when we were the target of the 8th Air Force. I was never so scared in my life. The ground vibrated and the walls shook. Through 10/10ths, the 8th did its work well, blasting the railroads and public utilities. We were without lights and water for eight hours. We were informed by the German authorities that nothing was hit except residential areas and churches, and that the infuriated people had lynched the air crews who were forced down in that locality. That should serve us as a warning against attempting any escapes. We were better off inside the wire. “That night, we were again in the Shelter, as the RAF came over, but was on its way to Berlin. Many the man here was severely wounded and the hospital and staff was inadequate. There was an English pilot who flew with artificial limbs. These, the Jerries took away every night as an escape prevention measure. Several of the men were severely burned around the face from oxygen aflame. One, a Captain Cook, so badly burned that his eyelids were gone, preventing sleep - only able to relax an hour or so every night. He left for a base hospital and plastic surgery. In the face of all this, my injuries were trivial and I ceased going on sick call. “While at Frankfurt, I met Capt. Robert L. Ager our Group Gunnery Officer, and Lt. (Henry A.)Wieser Group Bombardier, who came along on the 21st, expecting a milk run, flew with Lt. Cookus in ‘A’ Flight. In leaving the coast, they flew over Calais, were hit by flak. Cookus gave orders to bail out while he stayed with his ship and crash-landed in southern England. Hard luck for Ager and Wieser. One afternoon we were issued necessary clothing and a grip containing cigarettes, pipe and tobacco, extra socks and underwear, etc. We also got a Red Cross parcel to last a week, and told we were on our way. We were admonished not to make a demonstration or attract the attention of the public who were still plenty mad, Any attempt to escape and we would be shot. “Loaded onto trucks with plenty of guards, we were taken to the Depot where we had visual evidence of the recent bombing raid. We were loaded into a freight car on a siding, and as they locked us in, off went the siren heralding the approach of the RAF. There was great uneasiness among the Kriegies and a thorough testing of the locked doors and barred windows. It was obvious we could never get out that way, and it was a sigh of relief we gave when the train jerked into motion and pulled out of the yard. “That night we passed 20 miles south of Berlin and we could see it was a target of the RAF. The city was a glow of fire and flame. We had four guards in our car, well armed with automatic and machine gun pistols. They informed us our destination was Barth, Germany, and painted a glowing picture of same until we concluded we must be headed for a rest camp with recreation facilities. Later on, they offered us beer in exchange for coffee, and some of the boys did it, getting a very poor grade of beer, which was by now the national brew. This trip was our initial meeting with the Red Cross Food Parcel and with a German ration of bread, potatoes and salt, we were to become excellent cooks. “After three days and four nights, we found ourselves at Barth, Pom., Germany, greeted by a formidable guard detail and a dozen German-trained dogs. So I entered what was to be my home for next one and a half years: Stalag Luft I.”

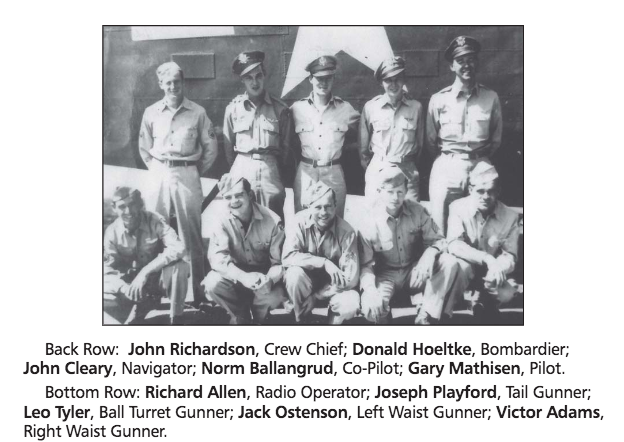

VALIANT LADY Crew

1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen Pilot KIA

2nd/Lt. Norris S. Ballangrud Co Pilot KIA

2nd/Lt. John J. Cleary Navigator POW

2nd/Lt. Donald R. Hoeltke Bombardier POW

T/Sgt. John L. Dickinson Engineer MIA/KIA

T/Sgt. Richard E. Allen Engineer POW

S/Sgt. Leo M. Tyler Gunner KIA

S/Sgt. Victor J. Adams Gunner KIA

S/Sgt. Jack N. Ostenson Gunner MIA/KIA

S/Sgt. Joseph E. Playford Gunner KIA

Memorial Service To Honor Flier.

A memorial service for Lt. Norris S. Ballangrud, who was killed in France, January 21, 1944, will be held at Bethlehem Lutheran Church Sunday at 11 A. M.

Lt. Ballangrud, who was pilot of a B-24, attended school at Silverton and at Benson Polytechnic School and was employed at the Bonneville Power Administration before his enlistment.

He is survived by his wife and daughter, his mother, Mrs. Dina Ballangrud, a brother, Arthur, of Kelso, Wash., and sisters, Alice Ballangrud, Della Stranix and Margaret Coppin.

---------------------------------------------------

Co Pilot 1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen KIA

Body Identified

Home: Portland, Oregon

Squadron: 68th 44th Bomb Group

Service# 0-681300

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

Pilot 1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen KIA

MACR #2359

Target: V-1 Sites, Pas Des Calais Area, Escalles Sur Buchy, France

Mission Date: 21-Jan-44

Serial Number: #42-7514

Aircraft Model B-24

Aircraft Letter:

Aircraft Name: VALIANT LADY

Location: France

Cause: enemy fighters.

Crew of 10 7 KIA 3 POW

Once again the weather was poor, with heavy cloud cover over most of this area of France. Normally, this should have been a relatively “safe” mission, being so close to the English Channel, but it turned out to be VERY costly. The 66th and 68th squadrons had their own specific target to hit and were determined to do so in spite of the clouds which were covering the small V-1 launching sites. Bombing altitude was at a very low 12,000 feet.

MACR briefly says that this aircraft, was hit on the sixth and last attack by the enemy fighters. The time was 1526 hours. This plane was seen to nose up and over the formation with the waist position burning profusely. No one reported seeing any parachutes. This was their 18th crew mission. Sgt. Leo M. Tyler, ball turret gunner, was (apparently) reported incorrectly as POW. He was later reported killed at Poix, Somme, France by the Department of the Army. Only three men survived to become POWs: Allen, Cleary, and Hoeltke. Relatives of Donald R. Hoeltke reported that only three men got out of the plane and one of these was very seriously injured (probably Allen). The plane was shot down in the area of Bruay, France. The crash site is located at Neuville-Ferrieres, 4 miles SSW of Neufchatel. When Lt. Hoeltke hit the ground, he was immediately surrounded by troops with about 18 bayonets shoved at him. There was no possibility of any attempt at evading capture. He was taken in for interrogation according to the usual procedure, but Donald learned that his interrogator had worked in the U.S. for several years, knew Al Holderman of the Gannett News, and had returned to Germany as a private pilot. Later, he was grounded and due to his excellent English, was made an interrogator of English and American POWs. Lt. Hoeltke’s widow stated that he had told her he thought that three men got out and parachuted, but one was critically wounded and could have died. He knew that Sgt. Tyler had been made a POW; their site of capture being about 45 miles south east of Calais, France. Lt. Hoeltke was later sent to Stalag Luft I, Barth and remained there until the end of the war. Lt. Cleary’s name was not mentioned. (See his account later on.)

Richard Allen wrote the following, not long before his death in 1947: “We were attacked by about 30 fighters over France near Path Colay on 21 January 1944 and shot down. I believe we went over our target about six times but I couldn’t be sure. Before we were hit by the fighters, I was flying Radio Operator (my position) when Sgt. Ostenson came up front to fix some trouble with the nose guns. He was our armament gunner. The pilot told me to take over his (Sgt. Ostenson’s place) until he came back; that was the left waist. “I no sooner plugged in my electric suit when the attack began. There were about seven planes in our squadron and I believe six of us got knocked down. When we got hit, I was shot through the leg and received a bullet in my spine. The other waist gunner S/Sgt. Victor Adams was also shot and as far as I could see, he was dead. The plane was all on fire from oxygen burning, and it brought me to my senses and I put my chute on and pulled myself up on the waist window. My interphone was shot out and I couldn’t tell if we were going to make it back or not. The plane

was vibrating violently. I saw Sgt. Playford run out of the tail turret, and he was all on fire. At the same time, Sgt. Tyler, our ball turret gunner started to come out. It all happened within a few seconds and in that time, the plane seemed to roll over and I let go and went out. I didn’t notice whether they had their parachutes on or not. I did not see Sgt. Dickinson as he was up front in the top turret. When I got on the ground, I was picked up and taken to a hospital where I saw my bombardier, Lt. Hoelke, and Lt. John Cleary (navigator) for a few minutes. Lt. Hoelke and Lt. Cleary had bad ankles from the parachute landings. Later, in the hospital, I met a crewmember from one of the other planes in our squadron and he said he saw our planes going down in a spin with flames coming out of the engines.”

The following information comes from a document written by a graves registration investigator named Howard E. Ephraim: “Contact was immediately made with the Mayor of Neuville-Ferrieres, Mr. Gonse, who was particularly well informed on all details pertaining to the crash of A/C 42-7514. He stated that he had seen the plan e crash, that three men bailed out, and that six men were removed in caskets by the German troops. That accounted for nine of the ten-man crew. He further declared that eight days later a dog, which had been attracted by the odor, indicated an additional set of remains which had been obscured by a sheet of aluminum. A guard had been posted at the wreckage of the plane and eventually all of the wreckage above ground was removed by German ordnance crews. No one at Neuville was aware of the fact that this last remains was removed, hence, it is considered possible that it was buried at the scene of the crash by the ordnance team. This account was verified by Mrs. Lefebre who also gave to the investigator the identification tag of Jack Ostenson, one of the unresolved casualties in the crash. This tag was found at the scene of the crash by Mme. Lefebre. A few days later, the Germans removed the wreckage. This definitely fixes the identity of the plane as that of A/C 42-7514.”

Lt. Cleary wrote the following account about the events of January 21, 1944: “Gentlemen, your target today is a milk run, a V-1 site, southeast of Neufchatel, France, only ten minutes over the enemy. Area escort provided by the 8th Air Force Fighter Command and British Spits. Altitude, 10,000 feet. Departure point is southeast corner of England. The 44th BG flight of 24 ships in two 12-ship boxes, will split into two flights of six each. Flight A, lead by Col. Dent; Deputy Lead Lt. Gilbert. Flight B lead by Lt. Williams, Deputy lead Lt. Mathisen. Good luck men. See you when you return. “Deputy lead, Flight B crossed enemy coast at Fecamp, on course, at altitude. The boxes have split for the different targets, and all are now in separate flights. I.P. in sight, three minutes to target. Light, scattered cumulus below, visibility .8. No flak, no fighters, all is well. Target in sight, obscured by small cumulus, so fly 360 degrees to let it clear. Time 1500. Flew continuous 360s, target is still isolated, but clearing. Time 1550. “Suddenly, ‘Waist to crew. Waist to crew. Enemy aircraft at 2:00 o’clock, low.’ Immediately B Flight tightened up the formation and hoped for the best. A quick glance revealed approximately 16 Me 109s and 35 FW 190s. A Flight was approximately three miles ahead and coming off the target. Do not believe they ‘dropped.’ “Then the enemy was up and because we were on the bomb run, they concentrated on us, leaving A flight alone. I knew from the ship’s vibration that all stations were manned and firing, but they are attacking from about 4 to 5 o’clock, low to level, working us over from the rear.“From the tail turret came the report (1) ‘Spelts going down, (2) There goes Starring. (3)They’ve got Howington!’ We were still on the bomb run and suddenly from the bombardier (Lt. Hoelke) came ‘Bombs Away!’“I heaved a sigh of relief to know that we were rid of them. Bank away to the left and head home. Then, over the interphone from the pilot (Mathisen). ‘Keep an eye on Sobotka. He’s hit.’ I verified this, noting all reports in the ship’s log, got a visual fix and informed the crew that if we could hold out for five more minutes, we would be clear and over the Channel to safety. I requested the pilot to summon assistance from our escort. He replied that he couldn’t do so. That was up to Lt. Williams in the lead ship. “Waist gunner then called in that Sobotka was going down, and then from the pilot, ‘They’re coming in again. Let’s get some of the bastards!’ All stations were firing and the ship gave a terrific lurch, banked to the right, and went into a slow, descending spiral as the enemy raked us from the nose to tail. A 20-mm exploded between the cockpit and nose, showering Lt. Hoelke and myself with light fragments. ‘We’ve had it!’ shouted Hoelke, as we checked things, and found all communications out. Our Nose Gunner, by now, had his turret aligned (so he could get out). Hoelke slid past me to the escape hatch, passed me my chute, and with the nose gunner behind me, we prepared to abandon ship. “I pulled the emergency release, and as the escape hatch flew away and to save time for the others, I stepped out into space, parachute in hand, intending to secure same during my fall. To my amazement, I still hung suspended in space, shoulders even with the fuselage bottom, with my head in the ship!! I was caught on my extra long interphone extension. Reaching up, I pulled myself aboard and while I cleared my phone, Hoelke reached over and put my parachute on me. As I re-jumped, I heard the nose gunner shout, "My chute! My chute!!" I fell through the air, spinning like a top while experimenting to find the best position. This proved to be on my back. “I felt like a feather in the air – there was no feeling of resistance, no planes were to be seen except my own, spinning. It crashed in a flaming roar. No other parachutes were in sight, and I felt sick about the other men. “There was no more gunfire to be heard, absolutely no sound at all. A celestial calm seemed to prevail. but coming to with a start, I pulled the ripcord. From my now upright position, I realized my chute was satisfactory, and the calm, sunlit terrain of France was sweet below. “As I neared the ground, I could see a farmer calculating my angle of fall, and as I neared there, he was reinforced by a dozen others. Then I clearly saw they were Germans of the Luftwaffe all around, with machine gun pistols. As I turned to keep them in sight, I hit the ground and my right foot buckled under me. The Germans were on me in a flash, spread-eagling me, they conducted a rapid search. Completed, I was assisted to arise. I reached to release my English type parachute harness, and seeing same was in the unlocked position, I grew suddenly weak. The Germans had to support me to prevent my collapsing. Had I but touched that buckle in the air, my parachute and I would have parted company! “Escorting me to the roadside, I was seated on the bank while a medical orderly administered some necessary first aid. My right foot was severely injured. Cutting away my flying boot, he applied a cold compress and assured me that there were no broken bones. My left arm was injured from a 20-mm, halfway up the arm from my wrist. It was just like a cut from a keen razor. Washing same, he applied a disinfectant and tied up same with adhesive. “I was then carried by my escort to their headquarters, and so learned that I was back at Neufchatel, having floated in my chute a distance of 35 kilometers from the Channel at Deippe. “Here I was the object of much curiosity and many would stroll by, then quickly snap a picture with their cameras. I was detained there for two hours, given my first cup of Ersatz, and met my first German Officer. He strode to the phone and having got his connection, yelled back and forth so loud and fiercely, I was sure they could hang up the phone and still continue the conversation. He studied me a moment, and then gave what I realized to be a description of the Group - Squadron insignia on my A-2 (flying jacket). Then, hanging up, he strode to where I sat and barked in excellent English, "What is the strength of your Group in men and ships?" “I just sat there and wondered if he really thought I would answer that. Evidently not, because as I silently sat there, he spun on his heels, marched out. After this, I relaxed, slept for half an hour, and then I was awakened by the entrance of a German field gendarmerie. He was the first adult-looking man I saw since being captured (all of the others being boys of extreme youth). “He took me in charge and seeing I could but hobble, he picked me up in his arms and carried me out to a car very similar to a Willys, where I promptly fell asleep again. This was probably much to the relief of my guard and his chauffeur. I awoke in Rouen and was taken to what appeared to be a Catholic hospital. “Upon being carried inside, I was overjoyed to see Sgt. Allen, my radio operator, who was in action as a waist gunner that day. He was lying on a stretcher, but sat up and gave me some additional information on the crew. Lt. Hoelke, bombardier, had been there recently, and like myself, had but minor wounds. No one else got out of the ship. The plane itself had communications out, hydraulics out, and the tail section was on fire. Richard, although shot through his body and legs, looked okay, and should, I believe, recover. To date, however, I have been unable to get any word of him. Taken to another room, I was treated for my leg and arm, given some vile potion to drink. My guard carried me to Police Headquarters in town where I met Lt. Hoelke and Sgt. Andrew Ross, of Sobotka's crew. Having the office to ourselves, except for a Jerry, who seemed to be acting as C.Q. and who talked to us by means of a German-English-French book of vocabulary, we talked. “We discussed the situation and came to the conclusion that the nose gunner may have had his chute on the escape hatch and same was lost when I pulled the emergency release; or else he left it at his regular position in the waist, and failed to get back there in time. The Germans had caught us square in the cockpit, getting both the pilot and co-pilot (Ballangrud), then raking the ship back clear to the tail. Like myself, Lt. Hoelke was captured as soon as he hit the ground. “We were finally served a meal of a hot, hideous soup, Ersatz and bread, which was the national Jerry war loaf. I promptly dug into same and immediately became nauseatingly sick, so that I left the rest of it untouched. The prospect of life on such stuff was distinctly unpleasant, and it was a relief when they showed us to a bed. It was a double bunk, with straw ticks, permitting four occupants in a cell 8' x 10'. I shall be eternally grateful to Sgt. Ross who took off my shoes, wrapped the blanket around me, as I was violently ill. “An hour later, the lights came on, chain and bolts withdrawn, and Lt. Fred Butler, navigator of Sobotka's crew, was shown in – to complete our happy home. “I awoke the next day feeling a new man, the shock and dazed condition having passed away. We were given what was to become our standard breakfast – Ersatz and bread. We loafed around the office being an object of curiosity to all the Jerries and French workers. Due to the heat in the room, I removed my A-2 jacket and coveralls. A sad mistake, because shortly thereafter, a guard detail came in and motioned us out, refusing to permit me to take my A-2. I have often wondered if it was recovered by the capturers of Rouen or kept by the Jerries as a souvenir. “We were ushered into an open truck with six guards, and transferred to the Bastille of Beauvais, a building with a 4 x 8 cubicle containing the usual prison bed, a small stove and a bedpan which stunk to high heaven. The room was daily swept out and stove remade by a British Senegalese, a slim giant who spoke a soft, musical English. He was captured in Africa, had made three escapes – one clear back to Africa, which was now controlled by Rommel. He told me about prison life – mail, Red Cross parcels, etc. Just before we left, he gave me a half can of Corn Beef. It was delicious, as by that time we were famished on the Jerry diet. “Here, I noticed that the Germans, despite a search, had overlooked my wallet, taking it out and destroying my A.G.O. card and secreted some 12 pounds Sterling in my belt. Lt. (William) Jones, Bombardier from Starring's crew, joined us here. “After four days at this hostelry. we started on our journey to the "Vaterland" via Paris. All was peaceful and serene in Gay Paree. Everyone seemed well dressed, well fed and fairly content, although we received many a sympathetic glance. We traveled in a compartment to Frankfurt-on-Main and were taken to Oberusal, a small village ten miles from Frankfurt. This was the Jerry interrogation center for captured Allied airmen. After a thorough search, which found the money in my belt, we were again thrown into solitary confinement. Next day, I was given a questionnaire to fill out, giving my name, rank, serial number, and home address. I left the remainder blank, and returned it to the Jerry. I was then informed that I would go to interrogation immediately. So preparing for a third degree of the worst sort, and all set to give battle, I was taken to another building and introduced to my Grand Inquisitor. To my amazement, he greeted me like a long-lost brother and spent the first half-hour discussing his wife and family in New York, as well as the fine times he had at Jones' Beach. “After that he switched to questioning: Route overseas, Personnel of the 44th BG, Cadet School, O.T.U., bases, and members of the crew. Upon refusing any information, he said that he knew the crew and if I would verify it, he would give me any information he had on them. All this time he was "feeding" me some abominable cigarettes, which being my first in a week, I thought were grand! “He produced a list of names and positions - and sure enough, it was the entire crew. I acknowledged it, and was told that all were dead except Hoelke and myself. He had no information on our radio operator, Sgt. Allen. He then produced a thick manual and spent a half-hour telling me all about my Group, both combat and ground personnel, etc. He told me we were starting to receive the new B-24 H & J's, knew the exact routes for flying overseas, training schools in the States, O.T.U. bases, etc. He concluded by saying, "So you see I actually know more than you do!" He was correct. He then remarked as he dismissed me, "Your Air Force is about to separate from the Army and Navy, similar to the R.A.F. and Luftwafte, and your new uniform is a light blue gabardine." To date, I have heard nothing to verify this. “I was returned to solitary and usual prison lunch at 1:00 and to my surprise, was again taken back to the interrogator. This time to meet half dozen German navigators who could speak no English. Through the interpreter, they requested info on "G,” the reliability of metro info, radio bearings and fixes. I grinned, smoked their cigarettes and explained that we depended strictly on D.R. and Pilotage, if weather permitted. They quickly lost interest and as I was dismissed, the guard was instructed to permit me to wash and shave. I was then told I would move to the Transit Camp in Frankfurt for shipment to a POW camp. “After a week’s time, the wash and shave was a heavenly gift and a natural necessity. Later the guard brought a book to my cell and the thought of electric lights was like looking forward to Christmas. He must have been exercising a sadly neglected sense of humor or else sincerely thought an airman could see in the dark. “That night was my first experience on the receiving end of an Allied Air Raid. The RAF came over, but it was merely a nuisance raid. Thirty Mosquitoes, with a "Cookie" each, (60 tons - some nuisance!). Locked in my cell, I felt like a caged animal. Next day I was transported to a transient camp at Frankfurt and received immediate medical attention, followed by an honest-to-goodness hot shower and a fine, hot meal of Corned Beef, mashed potatoes, cake, coffee, and cigarettes. Hooray! God's in his Heaven, All’s well with the world. “Here we had an air raid shelter, of which we made much use, especially on January 29th, 1944, when we were the target of the 8th Air Force. I was never so scared in my life. The ground vibrated and the walls shook. Through 10/10ths, the 8th did its work well, blasting the railroads and public utilities. We were without lights and water for eight hours. We were informed by the German authorities that nothing was hit except residential areas and churches, and that the infuriated people had lynched the air crews who were forced down in that locality. That should serve us as a warning against attempting any escapes. We were better off inside the wire. “That night, we were again in the Shelter, as the RAF came over, but was on its way to Berlin. Many the man here was severely wounded and the hospital and staff was inadequate. There was an English pilot who flew with artificial limbs. These, the Jerries took away every night as an escape prevention measure. Several of the men were severely burned around the face from oxygen aflame. One, a Captain Cook, so badly burned that his eyelids were gone, preventing sleep - only able to relax an hour or so every night. He left for a base hospital and plastic surgery. In the face of all this, my injuries were trivial and I ceased going on sick call. “While at Frankfurt, I met Capt. Robert L. Ager our Group Gunnery Officer, and Lt. (Henry A.)Wieser Group Bombardier, who came along on the 21st, expecting a milk run, flew with Lt. Cookus in ‘A’ Flight. In leaving the coast, they flew over Calais, were hit by flak. Cookus gave orders to bail out while he stayed with his ship and crash-landed in southern England. Hard luck for Ager and Wieser. One afternoon we were issued necessary clothing and a grip containing cigarettes, pipe and tobacco, extra socks and underwear, etc. We also got a Red Cross parcel to last a week, and told we were on our way. We were admonished not to make a demonstration or attract the attention of the public who were still plenty mad, Any attempt to escape and we would be shot. “Loaded onto trucks with plenty of guards, we were taken to the Depot where we had visual evidence of the recent bombing raid. We were loaded into a freight car on a siding, and as they locked us in, off went the siren heralding the approach of the RAF. There was great uneasiness among the Kriegies and a thorough testing of the locked doors and barred windows. It was obvious we could never get out that way, and it was a sigh of relief we gave when the train jerked into motion and pulled out of the yard. “That night we passed 20 miles south of Berlin and we could see it was a target of the RAF. The city was a glow of fire and flame. We had four guards in our car, well armed with automatic and machine gun pistols. They informed us our destination was Barth, Germany, and painted a glowing picture of same until we concluded we must be headed for a rest camp with recreation facilities. Later on, they offered us beer in exchange for coffee, and some of the boys did it, getting a very poor grade of beer, which was by now the national brew. This trip was our initial meeting with the Red Cross Food Parcel and with a German ration of bread, potatoes and salt, we were to become excellent cooks. “After three days and four nights, we found ourselves at Barth, Pom., Germany, greeted by a formidable guard detail and a dozen German-trained dogs. So I entered what was to be my home for next one and a half years: Stalag Luft I.”

VALIANT LADY Crew

1st/Lt. Gary M. Mathisen Pilot KIA

2nd/Lt. Norris S. Ballangrud Co Pilot KIA

2nd/Lt. John J. Cleary Navigator POW

2nd/Lt. Donald R. Hoeltke Bombardier POW

T/Sgt. John L. Dickinson Engineer MIA/KIA

T/Sgt. Richard E. Allen Engineer POW

S/Sgt. Leo M. Tyler Gunner KIA

S/Sgt. Victor J. Adams Gunner KIA

S/Sgt. Jack N. Ostenson Gunner MIA/KIA

S/Sgt. Joseph E. Playford Gunner KIA

Inscription

2LT, US ARMY AIR FORCES WORLD WAR II

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement