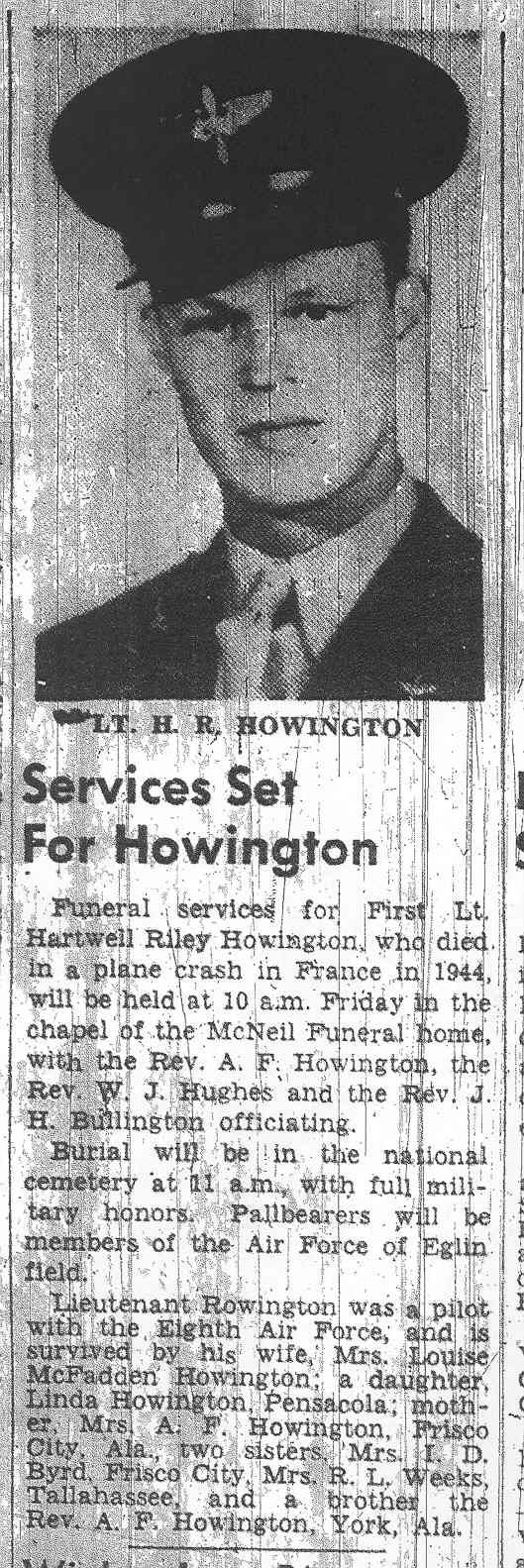

Pilot 1st/Lt. Hartwell R. Howington KIA

Hometown: Cantonment, Florida

Squadron: 68th 44th Bomb Group

Service# 0-800356

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

MACR #2357

Target: V-1 Sites, Pas Des Calais Area, Escalles Sur Buchy, France

Mission Date: 21-Jan-44

Serial Number: #42-7635

Aircraft Model B-24

Aircraft Letter:

Aircraft Name:RAM IT-DAM IT/ ARIES

Location: Normandy France

Cause: enemy aircraft Crew of 11 3KIA 1MIA 2POW 5EVD

Although all 44th BG planes took off at the same time, there were actually two target missions involved on this date, with two separate formations. Once again the weather was poor, with heavy cloud cover over most of this area of France. Normally, this should have been a relatively “safe” mission, being so close to the English Channel, but it turned out to be VERY costly. The 66th and 68th squadrons had their own specific target to hit and were determined to do so in spite of the clouds which were covering the small V-1 launching sites. Bombing altitude was at a very low 12,000 feet.

The 68th Squadron drew the “Tail-end Charlie” section of our formation and paid heavily for it. The 68th sent out seven aircraft and only three of them returned! Lt. Hartwell R. Howington, pilot of RAM IT-DAM IT, was hit during the third attack of the enemy aircraft, according to the MACR. It was observed to make a wide circle to the left, smoking, and went into a spin; one chute observed. But the fighter attacks were so intense at this time that no further observations were made or reported.

Sgt. Archie Barlow, engineer, relates his experiences that day, “All of our previous missions had been to Germany or Norway at high altitudes and extremely cold temperatures. This milk run was misnamed, for sure. We had a mid-morning call out and briefing instead of the usual pre-dawn awakening. “The target area was cloud covered when we arrived and we were on our third run,trying to get a good visual drop from about 12,000 feet when we first saw the German fighter formations. They made the first pass from off our right wing, then climbed ahead to make the next from about 11 o’clock, high. They must have raked us with several 20-mm hits. One exploded directly on the nose, killing the bombardier and navigator, and turning their compartment into an instant inferno. We think the co-pilot, Lt. Curtis, was killed by that very same blast. Another round must have gone off either on, or very near, the top turret I was manning, blowing off the plexiglass dome and sending shrapnel into my left chest and arm. I grabbed the seat release cable and dropped to the flight deck.

“The right wall above the radio station was on fire and Rosenblatt, the radio operator, was putting on his chute. He yelled that we had other fires in the waist area and had been ordered to bail out by the pilot. A quick glance forward showed the pilot, Howington, fighting the controls and was apparently unharmed. “I snapped on my chute, opened the door to the nose wheel compartment, and dropped down to be hit by heat and flames blowing back from the nose area. I stepped out on the catwalk, thankfully noting that the bomb bay doors were open and the bombs had been jettisoned. Just then Rosenblatt dropped down from the flight deck. I took one final glance into the cockpit. The pilot was looking back and motioning with one hand for us to jump.

“I actually jumped with the intention of free-falling for two to three thousand feet before opening my chute as we had been instructed to do many times while in training. But that falling sensation was such a shock to my system that I could not have been more that twenty to thirty feet beneath the plane when I changed my mind and gave a hearty yank on that cord. I wanted to know – and when I changed my mind and gave a hearty yank on that cord. I wanted to know – and immediately – whether or not that chute was good! It was, and the heavy jerk of the canopy’s opening was welcome relief. “I spent a few seconds trying to stop my wild oscillations, then looked off toward our plane. It was by then some distance off and probably at no more than 2,000 feet altitude. As I watched, it went into a steep glide and hit the ground in a fiery explosion. I saw only one chute between the plane and myself and figured that to be Rosenblatt’s. “I came down in a plowed field on the edge of a small village, spraining my ankle in landing. An elderly lady, once convinced that I was an American, led me into a nearby wooded area where we soon came upon Charles Blakley, one of our waist gunners. Speaking no English, the lady made us understand, through sign language and by using my watch, that we were to remain there until she returned at 9 o’clock that night. She left, going deeper into the woods.

“Within 15 minutes, German troops were searching for us. Three of them, talking quietly, but looking neither left or right, walked by us on a path no more than fifty feet away. Blakley was wearing a bright blue “Bunny Suit” electrically heated coveralls) that could have easily been seen. And as we waited for darkness, Blakley told me about a fire in the wing-root area above the bomb bay and that we had also lost one engine and another seemed damaged. The photographer had been the first to jump – from the rear hatch – and Blakley and Alfred Klein, the other waist gunners, jumped once they saw the belly and tail gunners get out of their turrets OK.”

Later that night they were joined with Rosenblatt and Klein, who also had been hidden nearby. And later still, they were told that the pilot had gotten out of the plane, but that he was killed on impact with the ground. He probably had bailed out too low for his chute to fully open. After a long and eventful trip that took until May, Sgt. Barlow arrived in Spain; June lst in London, soon on a flight home. I do remember her Crew Chief was Sgt. Lee. Also, we did have an eleventh man aboard that day. He was a photographer, I think named Reeves. He had loaded up in the rear just before take off and I never saw him then or later. When I came through an intelligence unit in London in June 1944, I was told that he, too, had just been through, having gotten out through Spain also.”

Note: The name “Queenie” is probably due to the aircraft’s call letter (Q).

S/Sgt. Earl E. Boggs said, “There definitely was a cameraman on the plane that morning. When we loaded into the plane, I went in through the rear camera hatch and the camera was raised up into the fuselage. It completely blocked off the tail section, so I had to wait until it had been lowered into position before I could get back into my tail turret. I remember telling the cameraman that if we had to bail out, he was not to raise the camera up into the plane and cut me off back there in the tail with no way to get out. Instead, he should salvo the darn thing. “When I came out of the turret to bail out, the camera and the cameraman were long gone. I do not remember the man’s name but have a listing of our crew that day – perhaps it was Ray P. Reeves. “I was hit in the right foot and ankle and spent the first month in a German field hospital in France. From there, I went to the interrogation center at Frankfurt. From there, by train, to Stalag Luft 6 at Memel, East Prussia and from there to Stalag Luft 4 near Stettin, Germany. The last three or four months were spent on the road. I was liberated May 3rd by the English. I think Heiter was in Stalag Luft 1.”Boggs was right that it was radio operator Ray P. Reeves who was operating that camera that day.

Ray P. Reeves informed, “I had been the radioman for Pappy Hill for many missions, including Ploesti and Weiner Neustadt, but was temporarily taken off combat to correct my nose and ear problems in December ‘43. As I had often operated a hand-held K-20 camera taking photos of our bomb strikes through the bomb bay on our missions, I became familiar with the photographers, etc. While recovering, I spent many hours in the photographic section helping and talking with the officer (Harvell?) My position on Hill’s crew in the 67th Squadron had been filled (by Sgt. Chase) so I was asked to fly as a photographer with the large camera at the rear hatch to try to take photos of German military installations to and from the target. My first mission – and last – as a photographer was with this 68th Squadron crew. “On the fifth circle to bomb, an old Me 109 converted night fighter attacked us, not from the nose, but from beneath and did not close, but fired from long range – and hit us, starting a fire. So I cleared the back hatch and jumped. I was eventually hidden by the French underground, was almost caught by the Gestapo in Paris, was escorted by train and then by bus towards the Spanish border. My guide abandoned me in the Pyrenees, where I nearly froze to death, but walked into Spain and was interned until an American Attaché came for me. To Gibralter, to England, and the Zone of Interior on 17 June 44, and “separated” on 24 November 1944.

During the war, Hartwell Howington’s brother received the following letter from a French girl named Gilberte Daumal of Lignieres-Chatelain, Somme, France: “I am an unknown French girl, but you will understand the reason why I dare to write to you. I think you have heard of death of your brother, Lt. Howington Hartwell. I am very sorry to revive your pain and I am deeply moved to tell you a sad story so difficult for me to translate in English “On the 21st of January 1944, at 3:00 o’clock in the afternoon, a big airplane fell, touched by antiaircraft near my small village somewhere in France. I perceived several parachutes in the sky, then with many people I went to see the remains of the airplane, which burned. “Suddenly, a Frenchman called us. He had uncovered a parachute. I was very afraid to approach near him. I did not want to see his face because I am a girl of feelings. People told me that he was not wounded, but his limbs broken by the downfall, the blood flowed from his ears, nose and mouth. A man who was working in the fields said to me to have seen him who struggled in the air because his parachute did not open. German soldiers were there. “They put his papers and perhaps jewels but I cannot assure to you I stayed aloof and I saw something which shone on the ground. Quickly I lowered and I picked it up. Cautiously, I looked. It was a wristwatch; there were some drops of blood outside and inside. I kept it in my hand precisely. I did not want that Germans would take it. I tried to learn his address, but I have been forbidden to approach. I just learned his name and birthday, but I swore to myself to send this dear souvenir to Howington’s family. At that time I did not know how very difficult it would be with this insufficient information. “The day after, I went again to the airplane. One or two airmen who could not jump out were on ground and burned. Germans put their remains into a small coffin. Lt. Howington was also placed in a large coffin. Soldiers carried him in a truck. His body passed in front of me. I crossed myself and the tragedy finished. “He was buried in the cemetery of Poix at 10 kilometers from my village and I knew his grave very well where I went often to bring flowers and pray for him and his family so far. “Now I am very sad because his grave is not there. American authority has taken away all bodies and transported them in a village in another district in order to make a military cemetery, but I know the name of this new place. “During the occupation, I could not make inquiries. I was waiting for the liberation. I learned that a French woman of French forces inside had lodged four American paratroopers who were in the same airplane. Lastly, I went and saw her. She gave four civilian addresses, so I wrote on the 18th of April [1945]. At the same time, I wrote to the American Embassy in Paris, which replied very quickly and could not give Howington’s family address. “I was beginning to despair when on the 13th of July, I received a lovely letter from one of Howington’s comrades, Charles Blakley. He indicated to me two addresses – yours and Mrs. Howington’s. I chose yours because I suppose, but I am not sure, if his wife knows this bad news. Please show her this letter if you like and tell me how I can send the wristwatch as soon as possible. “Destiny has confided a mission to me and it is nearly finished. Please excuse my bad English, but you must understand how difficult it is to write so long a letter. Give my regards to Mrs.Howington.”

As she promised in her letter, Mademoiselle Gilberte Daumal returned the watch to Howington’s widow. The women corresponded over the years and later Howington’s widow sent Gilberte material for her wedding dress.

RAM IT-DAM IT/ ARIES Crew

Hartwell R. Howington Pilot KIA

Hartwell R. Howington Pilot KIA

Herman M. Curtis Co Pilot KIA

Richard J. Kasten Navigator MIA/KIA

1st/Lt. Wayne D. Crowl Bombardier KIA

T/Sgt. Archie R. Barlow Jr. Engineer EVD

T/Sgt. Alvin A. Rosenblatt Radio/Op. EVD

S/Sgt. Nicholas M. Heiter POW Gunner

S/Sgt. Charles W. Blakeley EVD Gunner

S/Sgt. Alfred M. Klein EVD Gunner

S/Sgt. Earl E Boggs POW Gunner

T/Sgt. Ray P. Reeves EVD Gunner

11 December 1943 mission Emden, Germany crew member S/Sgt. Michael P. Mitsche was seriously wounded by flak. It was his fifth mission. He was transferred to the 77th Hospital on 21 December 1943 and did not return to Shipdham. He was sent back to the United States. Eight members of this crew were lost on 21 January 1944. Four of them, Howington, Curtis, Kastnen, and Crow, were killed in action. They were on the same aircraft with Heiter, Blakley, and Boggs, who survived. Schaeffer was killed when another aircraft was lost that day. From Hartwell Howington’s diary: “11 Dec. 1943. Went out again today – to Emden. Roughest mission yet. Mitsche hit direct with cannon shell. Blakley hit with fragments. 138 fighters shot down. Blakley got Purple Heart and recommended for soldier’s Medal. Mitsche got one fighter. Crew got two possibles. Mitsche got Purple Heart, OCL, and Air Medal. Ship hit with five cannon shells. O’Neill exploded right in front of us. Sky littered with burning and exploding Libs parts and fighters.” ‘Chick’ Blakley wrote the following about Michael Mitsche: “A 20-mm shell hit the edge of the ball turret sight glass. The result was that it took a great deal off his upper inner thigh muscle just below his groin. When I was with him in Milwaukee, we made most of his known bar rounds for him to show his beer buddies the guy that gave him in-air first aid ‘and the guy who saved his life.’ ” Blakley reported that Earl Boggs, the tail gunner, heard that Mitsche died in 1969.

1st/Lt. Howington also has a memorial Repton Methodist Church Cemetery Repton Conecuh County Alabama, it is unclear where he is buried.

Pilot 1st/Lt. Hartwell R. Howington KIA

Hometown: Cantonment, Florida

Squadron: 68th 44th Bomb Group

Service# 0-800356

Awards: Air Medal, Purple Heart

MACR #2357

Target: V-1 Sites, Pas Des Calais Area, Escalles Sur Buchy, France

Mission Date: 21-Jan-44

Serial Number: #42-7635

Aircraft Model B-24

Aircraft Letter:

Aircraft Name:RAM IT-DAM IT/ ARIES

Location: Normandy France

Cause: enemy aircraft Crew of 11 3KIA 1MIA 2POW 5EVD

Although all 44th BG planes took off at the same time, there were actually two target missions involved on this date, with two separate formations. Once again the weather was poor, with heavy cloud cover over most of this area of France. Normally, this should have been a relatively “safe” mission, being so close to the English Channel, but it turned out to be VERY costly. The 66th and 68th squadrons had their own specific target to hit and were determined to do so in spite of the clouds which were covering the small V-1 launching sites. Bombing altitude was at a very low 12,000 feet.

The 68th Squadron drew the “Tail-end Charlie” section of our formation and paid heavily for it. The 68th sent out seven aircraft and only three of them returned! Lt. Hartwell R. Howington, pilot of RAM IT-DAM IT, was hit during the third attack of the enemy aircraft, according to the MACR. It was observed to make a wide circle to the left, smoking, and went into a spin; one chute observed. But the fighter attacks were so intense at this time that no further observations were made or reported.

Sgt. Archie Barlow, engineer, relates his experiences that day, “All of our previous missions had been to Germany or Norway at high altitudes and extremely cold temperatures. This milk run was misnamed, for sure. We had a mid-morning call out and briefing instead of the usual pre-dawn awakening. “The target area was cloud covered when we arrived and we were on our third run,trying to get a good visual drop from about 12,000 feet when we first saw the German fighter formations. They made the first pass from off our right wing, then climbed ahead to make the next from about 11 o’clock, high. They must have raked us with several 20-mm hits. One exploded directly on the nose, killing the bombardier and navigator, and turning their compartment into an instant inferno. We think the co-pilot, Lt. Curtis, was killed by that very same blast. Another round must have gone off either on, or very near, the top turret I was manning, blowing off the plexiglass dome and sending shrapnel into my left chest and arm. I grabbed the seat release cable and dropped to the flight deck.

“The right wall above the radio station was on fire and Rosenblatt, the radio operator, was putting on his chute. He yelled that we had other fires in the waist area and had been ordered to bail out by the pilot. A quick glance forward showed the pilot, Howington, fighting the controls and was apparently unharmed. “I snapped on my chute, opened the door to the nose wheel compartment, and dropped down to be hit by heat and flames blowing back from the nose area. I stepped out on the catwalk, thankfully noting that the bomb bay doors were open and the bombs had been jettisoned. Just then Rosenblatt dropped down from the flight deck. I took one final glance into the cockpit. The pilot was looking back and motioning with one hand for us to jump.

“I actually jumped with the intention of free-falling for two to three thousand feet before opening my chute as we had been instructed to do many times while in training. But that falling sensation was such a shock to my system that I could not have been more that twenty to thirty feet beneath the plane when I changed my mind and gave a hearty yank on that cord. I wanted to know – and when I changed my mind and gave a hearty yank on that cord. I wanted to know – and immediately – whether or not that chute was good! It was, and the heavy jerk of the canopy’s opening was welcome relief. “I spent a few seconds trying to stop my wild oscillations, then looked off toward our plane. It was by then some distance off and probably at no more than 2,000 feet altitude. As I watched, it went into a steep glide and hit the ground in a fiery explosion. I saw only one chute between the plane and myself and figured that to be Rosenblatt’s. “I came down in a plowed field on the edge of a small village, spraining my ankle in landing. An elderly lady, once convinced that I was an American, led me into a nearby wooded area where we soon came upon Charles Blakley, one of our waist gunners. Speaking no English, the lady made us understand, through sign language and by using my watch, that we were to remain there until she returned at 9 o’clock that night. She left, going deeper into the woods.

“Within 15 minutes, German troops were searching for us. Three of them, talking quietly, but looking neither left or right, walked by us on a path no more than fifty feet away. Blakley was wearing a bright blue “Bunny Suit” electrically heated coveralls) that could have easily been seen. And as we waited for darkness, Blakley told me about a fire in the wing-root area above the bomb bay and that we had also lost one engine and another seemed damaged. The photographer had been the first to jump – from the rear hatch – and Blakley and Alfred Klein, the other waist gunners, jumped once they saw the belly and tail gunners get out of their turrets OK.”

Later that night they were joined with Rosenblatt and Klein, who also had been hidden nearby. And later still, they were told that the pilot had gotten out of the plane, but that he was killed on impact with the ground. He probably had bailed out too low for his chute to fully open. After a long and eventful trip that took until May, Sgt. Barlow arrived in Spain; June lst in London, soon on a flight home. I do remember her Crew Chief was Sgt. Lee. Also, we did have an eleventh man aboard that day. He was a photographer, I think named Reeves. He had loaded up in the rear just before take off and I never saw him then or later. When I came through an intelligence unit in London in June 1944, I was told that he, too, had just been through, having gotten out through Spain also.”

Note: The name “Queenie” is probably due to the aircraft’s call letter (Q).

S/Sgt. Earl E. Boggs said, “There definitely was a cameraman on the plane that morning. When we loaded into the plane, I went in through the rear camera hatch and the camera was raised up into the fuselage. It completely blocked off the tail section, so I had to wait until it had been lowered into position before I could get back into my tail turret. I remember telling the cameraman that if we had to bail out, he was not to raise the camera up into the plane and cut me off back there in the tail with no way to get out. Instead, he should salvo the darn thing. “When I came out of the turret to bail out, the camera and the cameraman were long gone. I do not remember the man’s name but have a listing of our crew that day – perhaps it was Ray P. Reeves. “I was hit in the right foot and ankle and spent the first month in a German field hospital in France. From there, I went to the interrogation center at Frankfurt. From there, by train, to Stalag Luft 6 at Memel, East Prussia and from there to Stalag Luft 4 near Stettin, Germany. The last three or four months were spent on the road. I was liberated May 3rd by the English. I think Heiter was in Stalag Luft 1.”Boggs was right that it was radio operator Ray P. Reeves who was operating that camera that day.

Ray P. Reeves informed, “I had been the radioman for Pappy Hill for many missions, including Ploesti and Weiner Neustadt, but was temporarily taken off combat to correct my nose and ear problems in December ‘43. As I had often operated a hand-held K-20 camera taking photos of our bomb strikes through the bomb bay on our missions, I became familiar with the photographers, etc. While recovering, I spent many hours in the photographic section helping and talking with the officer (Harvell?) My position on Hill’s crew in the 67th Squadron had been filled (by Sgt. Chase) so I was asked to fly as a photographer with the large camera at the rear hatch to try to take photos of German military installations to and from the target. My first mission – and last – as a photographer was with this 68th Squadron crew. “On the fifth circle to bomb, an old Me 109 converted night fighter attacked us, not from the nose, but from beneath and did not close, but fired from long range – and hit us, starting a fire. So I cleared the back hatch and jumped. I was eventually hidden by the French underground, was almost caught by the Gestapo in Paris, was escorted by train and then by bus towards the Spanish border. My guide abandoned me in the Pyrenees, where I nearly froze to death, but walked into Spain and was interned until an American Attaché came for me. To Gibralter, to England, and the Zone of Interior on 17 June 44, and “separated” on 24 November 1944.

During the war, Hartwell Howington’s brother received the following letter from a French girl named Gilberte Daumal of Lignieres-Chatelain, Somme, France: “I am an unknown French girl, but you will understand the reason why I dare to write to you. I think you have heard of death of your brother, Lt. Howington Hartwell. I am very sorry to revive your pain and I am deeply moved to tell you a sad story so difficult for me to translate in English “On the 21st of January 1944, at 3:00 o’clock in the afternoon, a big airplane fell, touched by antiaircraft near my small village somewhere in France. I perceived several parachutes in the sky, then with many people I went to see the remains of the airplane, which burned. “Suddenly, a Frenchman called us. He had uncovered a parachute. I was very afraid to approach near him. I did not want to see his face because I am a girl of feelings. People told me that he was not wounded, but his limbs broken by the downfall, the blood flowed from his ears, nose and mouth. A man who was working in the fields said to me to have seen him who struggled in the air because his parachute did not open. German soldiers were there. “They put his papers and perhaps jewels but I cannot assure to you I stayed aloof and I saw something which shone on the ground. Quickly I lowered and I picked it up. Cautiously, I looked. It was a wristwatch; there were some drops of blood outside and inside. I kept it in my hand precisely. I did not want that Germans would take it. I tried to learn his address, but I have been forbidden to approach. I just learned his name and birthday, but I swore to myself to send this dear souvenir to Howington’s family. At that time I did not know how very difficult it would be with this insufficient information. “The day after, I went again to the airplane. One or two airmen who could not jump out were on ground and burned. Germans put their remains into a small coffin. Lt. Howington was also placed in a large coffin. Soldiers carried him in a truck. His body passed in front of me. I crossed myself and the tragedy finished. “He was buried in the cemetery of Poix at 10 kilometers from my village and I knew his grave very well where I went often to bring flowers and pray for him and his family so far. “Now I am very sad because his grave is not there. American authority has taken away all bodies and transported them in a village in another district in order to make a military cemetery, but I know the name of this new place. “During the occupation, I could not make inquiries. I was waiting for the liberation. I learned that a French woman of French forces inside had lodged four American paratroopers who were in the same airplane. Lastly, I went and saw her. She gave four civilian addresses, so I wrote on the 18th of April [1945]. At the same time, I wrote to the American Embassy in Paris, which replied very quickly and could not give Howington’s family address. “I was beginning to despair when on the 13th of July, I received a lovely letter from one of Howington’s comrades, Charles Blakley. He indicated to me two addresses – yours and Mrs. Howington’s. I chose yours because I suppose, but I am not sure, if his wife knows this bad news. Please show her this letter if you like and tell me how I can send the wristwatch as soon as possible. “Destiny has confided a mission to me and it is nearly finished. Please excuse my bad English, but you must understand how difficult it is to write so long a letter. Give my regards to Mrs.Howington.”

As she promised in her letter, Mademoiselle Gilberte Daumal returned the watch to Howington’s widow. The women corresponded over the years and later Howington’s widow sent Gilberte material for her wedding dress.

RAM IT-DAM IT/ ARIES Crew

Hartwell R. Howington Pilot KIA

Hartwell R. Howington Pilot KIA

Herman M. Curtis Co Pilot KIA

Richard J. Kasten Navigator MIA/KIA

1st/Lt. Wayne D. Crowl Bombardier KIA

T/Sgt. Archie R. Barlow Jr. Engineer EVD

T/Sgt. Alvin A. Rosenblatt Radio/Op. EVD

S/Sgt. Nicholas M. Heiter POW Gunner

S/Sgt. Charles W. Blakeley EVD Gunner

S/Sgt. Alfred M. Klein EVD Gunner

S/Sgt. Earl E Boggs POW Gunner

T/Sgt. Ray P. Reeves EVD Gunner

11 December 1943 mission Emden, Germany crew member S/Sgt. Michael P. Mitsche was seriously wounded by flak. It was his fifth mission. He was transferred to the 77th Hospital on 21 December 1943 and did not return to Shipdham. He was sent back to the United States. Eight members of this crew were lost on 21 January 1944. Four of them, Howington, Curtis, Kastnen, and Crow, were killed in action. They were on the same aircraft with Heiter, Blakley, and Boggs, who survived. Schaeffer was killed when another aircraft was lost that day. From Hartwell Howington’s diary: “11 Dec. 1943. Went out again today – to Emden. Roughest mission yet. Mitsche hit direct with cannon shell. Blakley hit with fragments. 138 fighters shot down. Blakley got Purple Heart and recommended for soldier’s Medal. Mitsche got one fighter. Crew got two possibles. Mitsche got Purple Heart, OCL, and Air Medal. Ship hit with five cannon shells. O’Neill exploded right in front of us. Sky littered with burning and exploding Libs parts and fighters.” ‘Chick’ Blakley wrote the following about Michael Mitsche: “A 20-mm shell hit the edge of the ball turret sight glass. The result was that it took a great deal off his upper inner thigh muscle just below his groin. When I was with him in Milwaukee, we made most of his known bar rounds for him to show his beer buddies the guy that gave him in-air first aid ‘and the guy who saved his life.’ ” Blakley reported that Earl Boggs, the tail gunner, heard that Mitsche died in 1969.

1st/Lt. Howington also has a memorial Repton Methodist Church Cemetery Repton Conecuh County Alabama, it is unclear where he is buried.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement